|

| What is the relationship between skill, challenge and flow? |

One of the most attractive aspects of video games is the possibility to experience flow. This happens when a user engages in an activity that fits his set of skills while still maintaining a certain level of challenge. The individual then becomes so focused in the task that the outside world slowly starts to disappear. Flow can make people feel better about themselves, have fun and forget about their problems. This makes it one of the most desirable objectives for both gamers and developers. But what attributes are expected to produce flow?

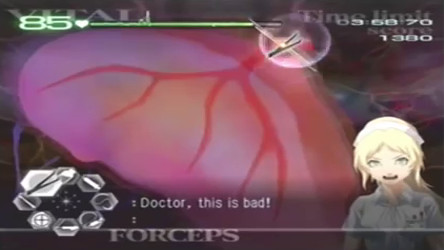

Most experts think there is a strong relationship between how skilled a player is, the amount of challenge he or she faces and the experience of flow. But finding what levels of challenge and skill can produce flow has not been that easy. For example: Since flow is associated with reward, then higher levels of difficulty should have a positive effect on flow, right? Well, not exactly. A recent experiment found no significant effects of difficulty on flow in a Tower Defense game (Schmierbach, Chung, Wu & Kim, 2012). Additionally, two experiments involving Wii games showed that the level of perceived challenge didn’t affect flow on “Trauma Center: New Blood” (a surgical simulator that uses haptic feedback on hand-held controllers) or “Need for Speed” (a racing game played, in this experiment, with a steering wheel) (Jin, 2011). It did, however, made the surgical instruments feel more real (physical presence) and increased the sensation of being inside a race (spatial presence), which had a significant effect on flow (Jin, 2011). This seems to suggest that challenge can have an indirect effect on flow. The high number of threats a player has to face in Ninja Gaiden, for example, could increase the importance of in-game events, making everything feel more real. This would make victories more rewarding but could also increase engagement, making the players forget about their problems.

|

| Ninja Gaiden’s difficulty could have increased both presence and flow. |

Cognitive skills, on the other hand, seem to have a rather unstable relationship with flow. A study on first person shooters, for example, revealed that the ability to hit a static target improved flow for players using a gamepad, but not for those using a motion controller (Bowman & Boyan, 2008). This suggests that the capacity of a skill to promote flow can be affected by different aspects of gameplay, like the type of interface being used. One possible explanation could be that when the characteristics of a game change, different abilities are required. In other words, the right set of abilities is more important than having many skills. This would increase performance and, therefore, the feeling of competence; both variables that have been associated with higher levels of flow (Bowman & Boyan, 2008; and Jin, 2012, respectively). The idea is congruent with an experiment in which players who rated better their ability to play a racing game achieved higher levels of flow while playing it (Jin, 2011). So, an ability for planning and leading organized attacks might improve your chances of experiencing flow in “World of Warcraft” and “League of Legends”, but it might not be that useful in a more chaotic environment like an online “Call of Duty” match.

|

| An ability that produces flow in a racing game could be useless in a surgical simulator. |

How much challenge or skill is needed for flow to occur? A series of studies on Wii titles showed that, more or less, low levels of challenge or skill tend to produce low levels of flow (Jin, 2011; 2012). This is especially clear in the case of “Need for Speed” (Jin, 2011) and “Need for Speed: Nitro” (Jin, 2012). This suggests that, at least in the case of racing games, a minimum level of demand or ability is required to experience flow. However, an experiment that measured the playfulness trait on people playing “Wii Fit” showed an interesting result. When playfulness was low, the effect of low challenge and skill on flow was, as expected, usually low (Jin, 2012). But when participants were highly playful, low levels of challenge and skill produced the highest levels of flow (Jin, 2012). This probably happens because the absence of challenge or skill means there will be little punishment for errors or reward for victories. This means that there will be less negative consequences if the player engages in free exploration, something that tends to attract highly playful people. So, if you start playing a Real Time Strategy games like Red Alert or StarCraft for the first time, try going through the tutorial campaign first. This will help you improve your skill, increasing your chances of experiencing flow later on. Unless you are the type of person that enjoys finding out the different features of a new game first; like listening the character’s voices or watching the different types of deaths.

|

| Forgetting the mission and exploring the surroundings can be fun too. |

Researchers believe that balance between challenge and skill should produce the highest levels of flow. This makes sense as a challenge superior to the player’s abilities would end up promoting frustration, and a level of difficulty inferior to the user’s skills would make the task boring. The hypothesis is supported by part of the evidence: Balance between skill and challenge has been associated with flow for computer games like “Pac-Man” (Engeser & Rheinberg, 2008) and “Bloons Tower Defense 4” (Schmierbach, Chung, Wu, & Kim, 2012), as well as for Wii titles like “Need for Speed” (Jin, 2011), “Need for Speed: Nitro” and “Mad World (a gory beat-em-up) (Jin, 2012). This didn’t happen, however, in the case of “Trauma Center: Second Opinion” and “Wii Fit” (Jin, 2012). One way to explain this is that specific game attributes made the experience of failure less negative or the positive feedback obtained from victories more rewarding, preventing a game that is too difficult or too easy to become less enjoyable. Maybe the absence of virtual enemies in “Trauma Center” made the player care less about losing and “Wii Fit” users were more interested in exploring the capabilities of the Kinect than scoring the highest score. In any case, evidence suggest that there is no sure way to provoke flow, but balance between challenge and skill is definitely a good start.

|

| Balance between challenge and skill seems to be less important in games like “Wii Fit”. |

It’s seems difficult to predict when or even if flow will happen. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t something we can do to increase our chances of either enter the state or provoke it. The first lesson we can obtain from the reviewed studies is that some skill is better than no skill. And while no player starts a game with a complete understanding of the mechanics, going through a tutorial or keeping the “hints” option activated could help users make a faster transition from “Wow, easy there!” to “Ok, let’s do this!”. The second lesson is that the relationship between challenge and skill seems to play an important role in the occurrence of flow. This means that it’s particularly important for developers to provide different difficulty levels the user can choose from, as well as carefully verify if the challenge increases with each stage just enough to match the player’s newly acquired skills. The final lesson we must remember is this: The circumstances of play can change what does and what doesn’t promote flow. Different game types and user preferences can, as we have seen, prompt unexpected situations, like a highly playful individual entering a deep state of flow just by ignoring all the objectives and do what he or she wants.

Flow is a complex phenomenon. Probably as complex as different types of games and players are out there. Finding a formula that consistently triggers intense and prolonged flow states in every single player might be impossible. But thanks to the work of both researchers and developers, we can expect flow to become a more accessible type of experience with every new generation of games.

References:

Bowman, N. D., & Boyan, A. C. (2008, May). Cognitive skill as a predictor of flow and presence in naturally mapped video games. Paper presented at the 58th annual convention of the International Communication Association, Montreal, Canada.

Engeser, S., & Rheinberg, F. (2008). Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 158-172. doi:10.1007/s11031-008-9102-4

Jin, S. A. (2011). I feel present. Therefore, I experience flow: A structural equation modeling approach to flow and presence in video games. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55(1), 114-136. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2011.546248

Jin, S. A. (2012). Toward integrative models of flow: Effects of performance, skill, challenge, playfulness, and presence on flow in video games. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(2), 169-186. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2012.678516

Schmierbach, M., Chung, M., Wu, M. & Kim, K., (2012, May). No one likes to lose: Game difficulty, motivation, immersion and enjoyment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Phoenix, AZ.